American historian, traveller and military man, Col. Theodore Ayrault Dodge wrote many interesting books - the list from modern equivalent of Alexandrine library collection - archive.org; and from his book 'Riders of Many Lands' comes a description of a bronco or horse of the US plains before coming of the Quarter Horse et al.

Well, let us read:

BRONCO:

''There is no horse superior to the bronco for endurance;

few are his equals. His only competitor in the equine

race is his lowly cousin, the ass, of whom I shall say much

anon. The bronco came by his toughness and grit natu-

rally enough; he got them from the Spanish stock of

Moorish descent*, the individuals of which breed, aban-

doned in American wilds in the sixteenth century by the

early searchers for gold and for the Fountain of Youth,

were his immediate ancestors; and his hardy life has, by

survival of the fittest, increased this endurance tenfold.

He is not handsome.

His middle-piece is distended by grass food; it is so loosely

joined to his quarters that one can scarcely understand where

he gets his weight-carrying capacity, and his hip is very short.

He has a hammer-head, partly due to the pronounced ewe-neck

which all plains or steppes horses seem to acquire by

their nomad life. He has a bit too much daylight under him, which

shows his good blood as well as the fact that he has had

generations of sharp and prolonged running to do. His

legs are naturally perfect, rather light in muscle and slen-

der in bone, but the bone is dense, the muscle of strong

quality, and the sinews firm. Still, in an Indian's hands

his legs finally give way at the knees from sharp stopping

with a gag-bit, and curbs will start on his houghs [hocks], for a

redskin will turn on a ten-cent piece.

The pony is naturally quick, but his master wants him to be

quicker. His hunting and all his sports require work which

outdoes polo. One form of racing is to place two long

parallel strips of buffalo-hide on the ground at an interval

of but a few feet,and, starting from a distance, to ride up

to these strips, ross the first, turn between the two, and

gallop back to the starting-point. A fraction of a second

lost on a turn loses the race.

Until one thinks of what it means, a twentieth part

of a second is no great loss. But take two horses of equal speed

in a hurdle race with twenty obstacles. One pauses at each

hurdle just one-twentieth of a second; the other flies his

hurdles with-out a pause. This lost second means that he

will be forty- five feet behind at the winning-post — four

good lengths. Another Indian sport is to ride up to a log

hung horizon- tally and just high enough to allow the pony

but not the rider to get under, touch it, and return.

If the pony is stopped too soon, the Indian loses time

in touching the log; if too late, he gets scraped off.

The sudden jerking of the pony on its haunches is sure

eventually both to start curbs or spavin, and to break his

knees. Still the pony retains wonderfully good legs considering.

The toughness and strength of the plains pony can

scarcely be exaggerated. He will live through a winter

that will kill the hardiest cattle. He worries through the

long months when the snow has covered up the bunch-

grass on a diet of cotton-wood boughs, which the Indian

cuts down for him; and though he emerges from this

ordeal a pretty sorry specimen of a horse, it takes but a

few weeks in the spring for him to get himself into splendid

condition and fit for the trials of the war-path. His

fast has done him good, as some say sea-sickness will do

him good who goes down to the sea in ships. He can go

unheard-of distances.

Colonel Dodge records an instance coming under his

observation where a pony carried the mail three hundred

miles in three consecutive nights, and back over the

same road the next week, and kept this up for six months

without loss of condition. He can carry any weight.

Mr. Parkman speaks of a chief known as Le Cochon,

on account of his three hundred pounds avoir- dupois,

who, nevertheless, rode his ponies as bravely as a

man of half the bulk. He as often carries two people as

one. There is simply no end to this wonderful product of

the prairies. He works many years. So long as he will

fat up in the spring, his age is immaterial to the Indian.

It has been claimed by some that the American climate

is, par excellence, adapted to the horse. California and

Kentucky vie for superiority, and both produce such wonderful

results as "Sunol" (famous trotting mare) and "Nancy Hanks.'' Man certainly

has done wonders with the horse upon our soil; and

alone the horse has done wonders for himself. I have

sought for great performances by horses in every land.

One hears wonderful traditions of speed and endurance

and much unsupported testimony elsewhere ; but for re-

corded distance and time, America easily bears off the palm.

We shall recur to this point hereafter. Ever since Brown-Sequard

discovered that he could not always kill an Ameri-

can rabbit by inserting a probe into its brain, and enunci-

ated the doctrine of the superior energy and endurance of

the American mammal, facts have been accumulating to

prove his position sound.

One peculiarity of the pony is his absence of crest. His

ewe-neck suggests the curious query of what has become

of the high, well-shaped neck of his ancestor the Barb*. I

was on the point of saying arched neck — but this is the

one thing which the Arabian or Barb rarely has, being

ridden with a bit which keeps his nose in the air. But he

has a peculiarly fine neck and wide, deep, open throttle of

perfect shape, and with bit and bridoon carries his head

just right. There are two ways of accounting for the

ewe-neck.

The Indian's gag-bit, invariably applied with

a jerk, throws up the pony's head instead of bringing it

down, as the slow and light application of the school-curb

will do, and this, it is thought by many, tends to develop

the ewe-neck. But this is scarcely a theory which can be

borne out by the facts, for the Arabian retains his fine

crest under the same course of treatment. A more suffi-

cient reason may be found in the fact that the starvation

which the pony annually undergoes in the winter months

tends to deplete him of every superfluous ounce of flesh

wherever it may lie. The crest in the horse is mostly

meat, and its annual depletion, never quite replaced, has

finally brought down the Indian pony's neck nearer to the

outline of the skeleton. It was with much ado under his

scant diet that the pony held on to life during the winter;

he could not scrape together enough food to flesh up a

merely ornamental appendage like a crest. Most Moors

and Arabs, on the other hand, prize the beauty of the high-

built neck, and breed for it ; and their steeds are far better

fed. There is rarely snow where they dwell; forage

of some kind is to be had in the oases, and the master

always stores up some barley and straw for his steed; or in

case of need will starve his daughters to feed his mares.

The Indian cares for his pony only for what he can do

for him, and once lost, the crest would with difficulty be

replaced, for few Indians have any conception of breeding.

The bronco's mean crest is distressing, but it is in inverse

ratio to his endurance and usefulness. Well fed and cared

for, he will regain his crest to a marked extent.''

______________________________________________

*

Juan Carlos Altamirano on Horses of La Conquista

Dr. Phil Sponenberg on Spanish Colonial Horse

Iberian horses genetics

eg The Origins of Iberian Horses Assessed via Mitochondrial DNA

****

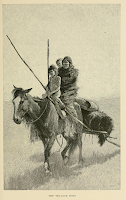

Prints by Frederic Remington and one by Rufus Fairchild Zogbaum

No comments:

Post a Comment